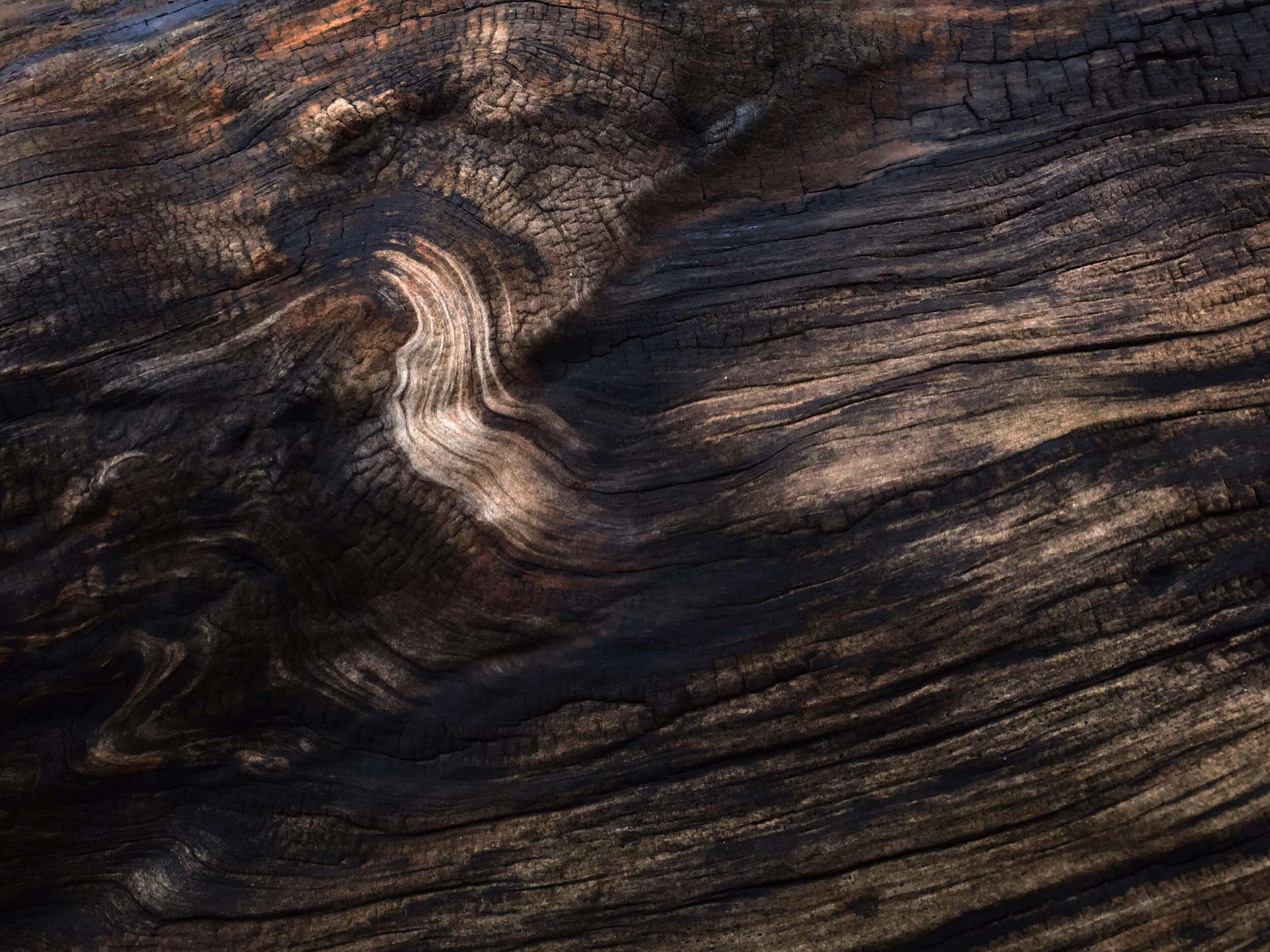

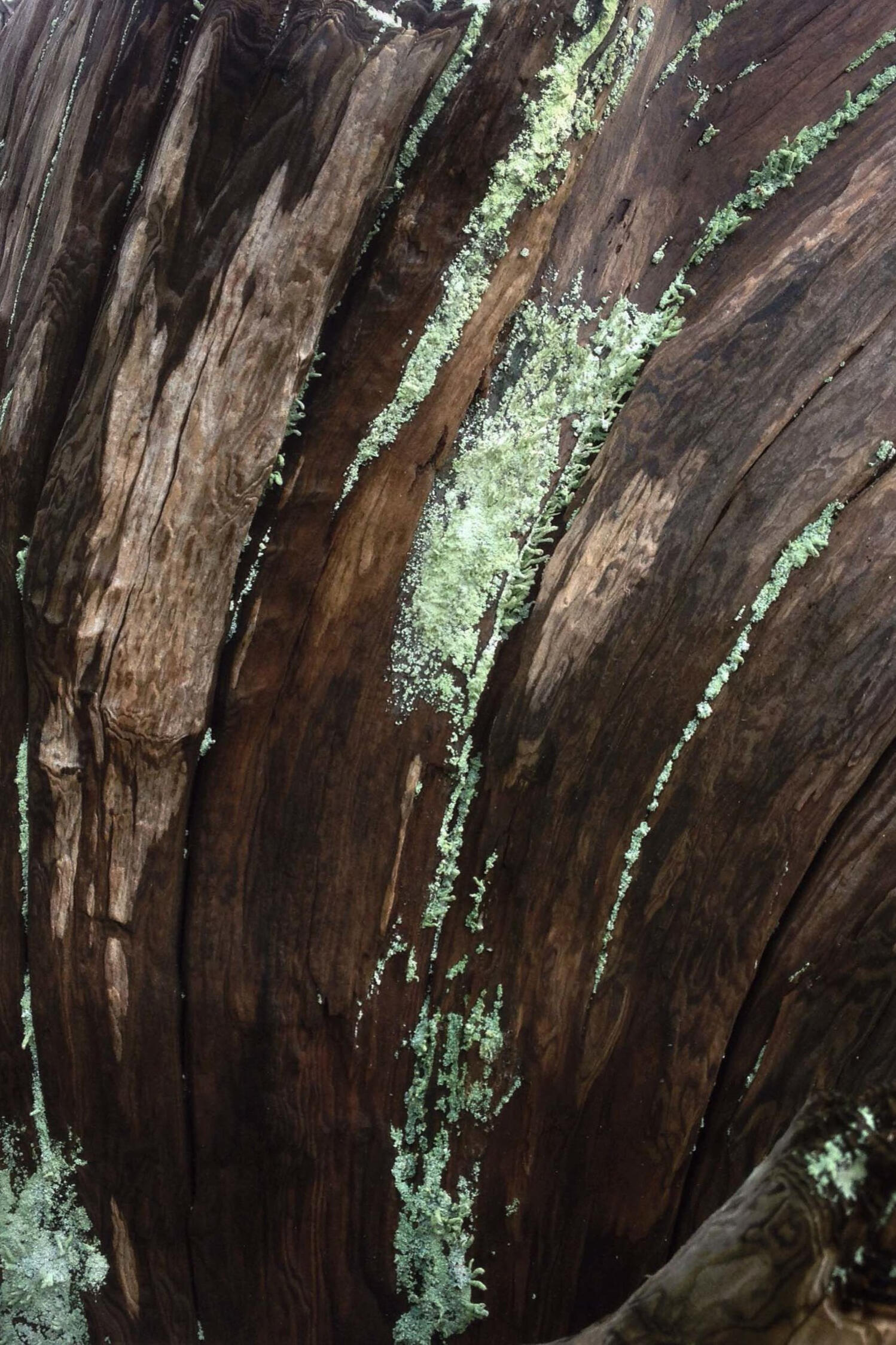

Driftwood Poetry

Journal - Vol. 3

Poems by Will Davies, Liana Esau,

Blythe Hutchcroft, Chris Campanelli,

and Derek WittenPhotos by Tim Andries

I. Hidden Things

Will Davies

Low Tide

Mouldering gods, in ages past,

turned this sand with yellow nails.

Post and long-abandoned lintel lined

the beach in worshipful rows.Cruel tyrant gods, their monoliths

decaying across the sound:

black and rusted ruby hulks.

The tide is low, is long.And past the tide, a row of herons stands

as sentinel to our deserted vows.

With toes I test the pools and make my way

to that stretch of sand, the low tidelands.As I cross the midden of tides,

the ghosts of the holy books

scatter, gulls, age-feathered pages

torn loose to hang on the breeze.Fishermen stride to the West, picking

their steps like herons, as though they remembered,

as though they still possessed

the end of this tide, this brief time.Soon, they are driven toward the shore

by rising waves, and I am left on a bank of sand,

the sea swimming against my calves

and herons standing past my reach.The elder bird has spread its wings,

has seen some thing that I have not.

It turns and the wind lifts it,

as it must, as the tongue of the drake commands.Its long limbs slip through the waves.

It is speaking, in its peculiar tongue,

to the sentinel – neck bent against her

side in deference – posted out to the East.I should return, I should turn

towards the shore; I have strayed

too far, too long and great gods sleep,

shrouded in weeds, only so long.

The herons remind that we are

where we have been, walkers on forgotten

mausoleums to cruel gods, mouldering tyrants.

City

I skate my fingers across your skin,

like a city laid, whole cloth, before me.

Your veins are hidden electric wires,

pulsing with quiet messages.

Districts are marked with peaked basilicas;

I parse their upraised crosses.I shower the city streets

with a thundering storm of kisses,

smelling the earthy petrichor your skin

exudes. I am hungry to explore

every alley and suburb of your expanse.Who laid out your foundations?

Who planned your zoning, when shops would open,

or skyscrapers rise, like your lips to mine?

But left room for parks and forests,

left young weeping willows to shade

the river valley that runs between.Between us is only atmosphere.

I have come up from the ocean and I

wait for my spell to be broken.

Your breath is heavy against my neck,

and my lips are cool; I could stay

for weeks, if the weather stays this way.

Parallax

The earth parallaxes, vanishes

beneath its own horizon,

then rises in night-sky mountains,

leaving scarce space for fields of stratus.This space of ocean and sky is broken

by corners of continental shelves,

where dirt has collected, where

birds have nested and left their effluence,

moss and grasses invaded, then trees have risen

and crowded their corners with all that is living.Above those highest bastions of earth,

behemoths of cloud crawl on

short tendrils across the treetops.

On Mount Elphinstone they grasp

at small deer and frightened owls,

making their homes in pine and fir.And even these loom

high above my sight, for I

am a man in a world of giants;

ancient trees beset by storms,

and these resting on islands, yet

young beside the ocean, covering

the earth against which

my eyes parallax.

Rain on the Harbour

Out on the island, expiring alone, I was

choking on the scent of yellow cedar.

It gave me the chills, a fever, a feeling

that the trees were looking askance at me.I wanted to call you. I thought

that you might draw the poison out,

as you had done before, but I lay

silent, and watched the rain take the harbour over.I must have finally perished there, for,

upon returning, I have been wandering

through empty streets, reeling with

fragrant magnolia. It is three in the morning.Has nobody seen me?

Has no one seen my warm breath straying through the silence?I rest again and my body feels –

not refreshed – but empty of death.

My neighbours must be working already,

the birds must have flown early this year,

main roads lie empty, washed in light,

like five in the morning when bakers and

mailmen have yet to rise.No church bells chime, no wires hum.

The city is all on holiday.

No cars run like rivers in their canals,

mechanics stay locked in garages,

shopkeepers don’t stock their shelves.This is not a dream that I may merely wake from.

Birds will emerge eventually from cracks in walls

where they lodged, and voices will drift

from opening shops, busses will

run again. But the silence that you gave me

stays, like ink beat into my skin, like

rain falling across the harbour, out on the island

where I still lie, expiring.

II. Touch

Liana Esau

Procedure

The cardiologist needs

assistance so I pull on the long

sleeves of a barrier

gown and obscure

my hands, my face, my feet

with plastic and paper.To the right hand of the doctor

I am a tall shadow behind the sterile field.

My hand to hand

over whatever he asks,

in each stage

deliberate and precise.“A strange case here,”

he comments offhand,

“the leak of blood is suffocating this heart.”

His fingers point to the chest before us, draped

in blue cloth. And so

we begin with a little anesthetic,

then a great mess

of piercing.But it ends how it always does.A small needle

crescent moon in the hand

of the quilter, a deft

loop of silken thread, a curled

finger knots it

off to attach the

red drain.The doctor leaves and I stay after to wrap

the neat wound in translucent plastic:

The man with the heart opens

his eyes.And I am only ashamed when

I see

that he sees

two small splashes

of his blood on my right

thigh.

Witness

I.

This morning my eyes are deeplocked

on a whiteout sky. Prayer leaks like water

from my cupped hands—I hope

not to be afraid.This morning God is obvious

the snow is falling soft

over a long row of poplars

in parallel punctuation,

To whom shall you go?

By noon I give up hope.

We are all dying to do the right thing.II.

We met at a long table and they

asked what I brought to the table.

I’ve seen a lot of death, I said.

And that’s something, I suppose.I remember there was a low swung moon

in August, swear to God bigger

than my face and red as blood.

It was slowly losing ground to

the deep stubble of a cornfield.

I stopped the car, a blue heron was

bent, listening.III.

One morning God spoke to me

and said

and said

And that’s something, I suppose.When I blow out the wick of a candle

smoke curls into a language.

Now the snow rises above the window seam

the poplars are bowed, a whisper

Whose mouth do you feed?

Who do you love?

And the world is quiet for a long time.

Host

I am coming

to learn out of my own

loneliness that

this strong cartilage

cording (meshing together our ribs

in lines

in lines,

sealing both breathing and beating

blood) is not meant to stay

knit-shut, butto open.

and in its shuddering, shuttering

we are necessarily

invaded,

this is our hospitality.Yet before there can be fear--

while I am still in the kitchen

thinking

about these things and adding

yeast to warm water--

and by the witness of the fruit

basket and the kneading bowl’s rounded

rim I am surprised to find

myself filling, not

emptying.

III. A Red Wing Rose

in the Darkness

Blythe Hutchcroft

FOR THE ARBUTUS TREE ON NORTH COVE ROAD, 1997

There was a chapel but I don’t remember what we said in it.

Instead, I remember the pancake coloured carpet,

the crack-slap of pellet rain on the hall’s tin roof,

how my limbs moved in the field.Here I glimpsed the shape of your name.

Here I sounded mine out, against a cracker on my tongue.While collecting spools of copper bark,

something untangled from within my frame:

a length of belly laughter,

my swimsuit-stomach flowering like a Jiffy Pop in flame.That summer something reached a fathom

for which we have no sign and crawled inside

my ribs to build its home. No clunky word

to contain that which it signified.

Just easy breath, a whisper’s bloom.I don’t know what draws us to the things we end up loving.

I do know that I buried treasure in those wide branches.

I was obliged, a tide stitched onto the warm rocks of her shore.

JESUS, ONCE MORE DEEPLY MOVED, CAME TO THE TOMB

1.

Mary fell at His feet on her brother’s behalf

as if to wipe them with her tears.Where were you, she cried on repeat.Was it a breach of His contract? The one

gift He swore to save for Himself,

moved by loss to share it?The stages of sorrow were on shuffle,

so Jesus chose denial

and wept.See how He loved him!Grief breathed on Lazarus

as Jesus said, “he’s only sleeping,”

and remembered he was dust.The one He loved came out like a scarecrow

to a crowd of expectant friends.

It was a race to see who could peel off

those strips of linen quickest.2.

And when it finally rains on Saint Catherine’s Street,

I think of Todd’s broad shoulders bending low.Damon mouths something but no sense arrives.He bikes to a Delta bayou,

sits next to a field of geese,

tries praying, plants a tree.Damon wonders if these are

the same geese who flew over his son’s body

on the Lions Gate bridge in May.Do they inquire after your sadness?One shuffles up, its long neck sweeping

like a branch of indoor plant

and blinks as if to say,

“There was nothing we could do.”Our friend is dust and soot,

mixing with the dirt at Fred Gingell park.

He was raised as a Japanese maple.

His new small hands left us wanting more.3.

There was no account of Lazarus’s second death,

someone tells me, so we wonder if he’s hiding

in some unmapped forest in Russia

modifying his hobbies until we all catch up.Oh, and when we do!Ashes will return to ashes like old friends

who have been apart too long.

FEBRUARY

1.

I did not wake up thinking of your body,

or your mother’s grief that rattled through

the phone as her thick sorrow failed to clarifywho had jumped and where and why.

Instead I woke up pawing through old

boxes piled high and wondered which oneheld my whisks, and whether or not we had any milk.

It wasn’t until later—much later,

thumbing pomegranate rind that afternoon—that I remembered my own small grief.

Rinsing garnet seeds, little clusters of

your sadness, I imagine the fall—that your contorted landing failed to parallel your

tone, which always signified poise, ease.

I imagine your soft body, rearranged likesome outstretched Adam reaching for its source.

Over time, I think, if we had left you there, your

skin might thicken, not unlike this rind, to encase

your broken bones like hollow, treasured gifts,

and when we find and pick you up, a rail of peanut brittle,

you rattle with mementos of your own Adamic loss.2.

Even though I did not wake up thinking of your body,

which is not at the service today,

I think I started to understand why

people want to be scattered in the graves

of their young hope. Like Powell River,

the summer we were both thirteen and

ripe with the urge of all things. Do you remember how

we clambered in your row boat, thick-thumbed with desire,

to take turns pulling each other in sunned tires

crudely fastened to the stern? When this game failed

we ran inside, heaving fistfuls of blackberries

on the counter for your mother, saying,

“That did not work. Can we make a pie?”3.

Eleven years later you tell her to “Pick up

the milk. I fed the dog.” That was your

last gift to her—a feigned sense of security—

as you, pulling weight from your shoulders,

plunge from one absence to another.

ON GRIEF

Yours snuck in

through the kitchen window—

the one we clambered out of, spilling onto

the warm stucco of your roof.

We could sit for hours, watching

small-town rush hour wade

through honeyed, heavy light.Your mind flitted like a whiskey jack that night

as you wondered out loud

about the nature of being wrong.Our legs, splayed like a pair of sandbox kids,

didn’t notice the gravel as it gathered itself

onto the backs of our knees.

My body sank into the palm of dusk

but yours darted inside to do the dishes,

sifting through regret stored up as stacks of hay

in some far away barn.I’m sorry for what I didn’t say.

I was distracted by the animals our shadows made

in the muffled light of new summer.What I should have said is this:

may grace trump our long-held belief

that someone is keeping score.

May your sadness run out of steam and collapse.

MOUNTAIN

Bright cloud,

I am the bride of my unknowing of you.

A listening skin,

breathed bones,

I clunk

at my own saying.

To be sure

I did not recognize you,

luminous as the blue edge of what I see.But be near.See, I have set the table for you.

I have poured you a glass of water. I am

preparing a place for you preparing

a place for me.

Come,

I have built you a shelter.

IV. Beautitudes

Chris Campanelli

An April Morning Missed

The sun would shine its

mid-morning rays across me,

nine years old, alone,

and stretched out on the

plush blue carpet floor.I used to lay long in that spot,

look up, and in the dust motes drifting,

recognize the very pulp of heaven--

angels’ fast descending--

and stay until light on my skin

suffused me with its soaring calm.That same light comes each year, although

that window and its house were razed.

That sun today shines on a door

I keep shut to construct my praise.

To The Measure

For T.C.When I walked in I knew it was the end.

An oxygen mask covered up your mouth.

Your body jerked upwards to take each breath,

each stark intrusion on your slump toward silence.

Then suddenly that struggle when your breathing

quickened, beeps sped up to trills, the nurse

rushed in to see you as you turned a purple-

red from head to toe, contorted, arched back

stayed there for a stunning fifteen seconds

until phlegm and blood welled from your lungs and gushed

into your mask. Your body’s self-defence

was what displaced your breath, and so your life:

an innate will to live which did not yield,

till it had filled your body to the measure.

Struggle

i.

I am a soul,

I have a body.I am a body,

I have a soul.I am a self,

I have a body, have a soul, have a spirit,

for that matter have a mind.I’ve sold myself upon the notion that

this overwhelming question needs an answer,

but I start to wonder now

if it can ever be sussed out,for I want to nod agreement to the

aforementioned definitionsbut I find they stir in me an argument

between my soul, body, and spirit,

as to who has the rights to define.I live, then, as an argument,

which likely will not be resolved

and must await arraignment on my day of death.

Our day of death.And still it remains up to me

to make arrangements

for that final day of rest,

so what should I expect?My body will be silent in its wooden bed,

the velvet inches from my

breathless mouth,

my then unthinking head—

spiritless, listless,

and (finally) selfless.Will my soul hover there above?

Will it remain dormant within?

Or else will it ascend

till all times end,

awaiting when it can

descend with heaven’s host,

and join again my lifeless frame

as it is called out from the ground

at the triumphant trumpets’ sound?Or will that be the day I’ll find that

I was only body after all?

(Except there’ll be no I to find that out).I think I cannot know yet what I am.ii.

Still, I must play a role upon this stage.The sages warn this role should not be co-opted

by any brittle code or written rule,

because only a living role contains

the power to make a scattered person whole.Such roles can make you free

precisely as they free you up from

needing always to be right.For even if a playwright writes to

reckon with the hubristic woe of striving up against

ones predetermined fate,

the actor,

for a fleeting moment,

when his spirits rise within the contours

of his fiction-freedom will discover there a fittingness,

a flaring at an unknown edge--

the flash of his own possibility.

Such acts actualize a mystery.I play and write these roles therefore

to free myself from what I lose

to the abyss of needing to be right.iii.

Sometimes though, I write to keep

from playing a role, or being a self,

and try to bury play within a careful turn of phrase,only to find the drama shines out plainly

when I have to test if these phrases of mine

are true.To do that, I must see that what I say

for me could just as well be said for you;the drama is what happens when I

struggle for a rhyme between us two.To put in words a sight in which I am

a mirrored you requires a raid uponthe unseen in the seen. My

self, my

soul, my

body, mind, my

heart, all of it’scaught up in one action, as I play

a Jacob, wrestling an unnamed manbeside an ancient ever-flowing stream.

An Aaronic Blessing

What is it in the human face that sends

these shivers trilling through her tiny frame,

and beaming through her cheeks, her eyes, her chin,

like water pooling in a curve of stone?

How does this one who has no words, who is

just lately gathered out of nothingness,

read happiness so readily and have

an instinct to respond in kind to us?

Do cheekbones speak? What words do eyes declare?

Or are these the primary means of speech?

From what I see, her mother’s glanced-goodwill

is gathered in and returned to its source,

as if the act of looking on someone

manifests a power of response.

V. Sound Ladder

Derek Witten

Acreage

April late the harrowing and sowing;

by the belly of June the sandhill

cranes arrived. Biking downwith Dad to get a better look,

we watched their slender shapes against

the soft-green shoots of early barley.Strange birds, their bobbing forward

heads at every step, their barn-red

ball-caps and divided call, a rustygate hinged into a strident trill

sounding several sections off.

The racket proving insufficientto unsheathe the swelling kernel of the prairie,

there is no splintered echo, just a fade

and silent, rising germination.That night, the window cracked, I’m wrapped

and warm within a single sheet,

and listening to the thunder growfrom guttural churn to perfect certainty--

the cranes’ calls deepened and magnified

from resting on the fertile air.(Acreage was first published in Crux, Summer 2015, Vol. 51, No. 2)

Sound Ladder

Here the clouds spend shapeless days dealing

winter’s portions with a teacher’s hand.

Strange to see them coming drunk and muscularthis afternoon above the campus library.

They bear me back across the Rockies, back

to boyhood, the uncomplicated disappointmentof a canceled game. The rain comes gusted

like blown silk, turning the shale from sunpink

Spanish tile to maroon, while parents shuffleoff the bleachers, coats over their heads:

seal up the bag of sunflower seeds, hurried

sips of whiskey from the travel mugs.Let us play. But back to the Astro van,

cleats on gravel, bats and helmets clink

in time with coach’s step. Before the slidingdoor has shut we hear the game begin

without us: wind-rush through the batting helmet,

the leather, wrapped and stitched, resounding offaluminum, the sound shimmering

off every rattled particle of sky.

Someone must have thrown a silent pitch.

Wing Light

Our pilot on the intercom:

“I’ll be turning off the North wing’s lightso you can see the lights

behind it.” Rising thumbs push off reading lights.

so I suspect they bow like me

against the cool oval.Aurora borealis—apparent stillness

in slow shaping,finding again a cracked

and hidden faculty in me.Have I forgotten the online checkbox

Where all these airport strangersMust have clicked assent?

“natural phenomenafor which you will revoke

your right to basic airline safety.”I admit there could

have been a clause, sunk

deep within the terms and conditions.Either way the expectedness of it all

was as arresting as the lights:it’s a rare bird but its migration is familiar.

Night in the Rockies

David Thompson Highway headed west,

as navy swells into the crow-black sky

and gradual hills break and jut immensely.I pluck a shiny pinion of the fleeing dark,

and sense the sheltered revels of the night,

when clouds wound down through pineson mountain banks to waltz slow

and ghostly on the robin-egg shell of

Abram Lake; when Mount Assiniboinebecame a Ktunaxa arrowhead

aimed skyward, back pulled flush against

the ridgeline, taut and searching,each night let fly at star-tipped

Mista Muskwa on his sky-line run,

restrung before the bald sun came

and wrestled shadows back to shape.

Driftwood Poetry

Journal - Vol. 2

Poems by Katrina Murphy, Natalie McNeill,

and Megan DrevetsPhotos by Kat Grabowski

Driftwood Poetry

Journal - Vol. 1

Poems by Cameron Reed, Derek Witten,

Christoph Sanz and Will DaviesPhotos by Tim Andries